Anvil used to study how trade can reduce volatilities in crop supply

A researcher from Purdue University used the Anvil supercomputer to study climate-induced volatility in crop production and identify the role of potential adaptation strategies for reducing future risk. The results of this research, notably that international trade can reduce volatility, are crucial for global food security as well as regional resilience.

Dr. Iman Haqiqi  is Lead Research Economist in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Purdue University. His research leverages high-performance computing (HPC) resources to study international trade, environmental, and resource economics, with a focus on global change and sustainability. Recently, Haqiqi utilized Anvil, one of Purdue’s most powerful supercomputers, to explore how strategic trade partnerships can buffer the risk of crop market volatility stemming from increased heat stress.

is Lead Research Economist in the Department of Agricultural Economics at Purdue University. His research leverages high-performance computing (HPC) resources to study international trade, environmental, and resource economics, with a focus on global change and sustainability. Recently, Haqiqi utilized Anvil, one of Purdue’s most powerful supercomputers, to explore how strategic trade partnerships can buffer the risk of crop market volatility stemming from increased heat stress.

Heat stress is a significant concern for crop production. When plants are exposed to excessive heat for prolonged periods, they can exhibit numerous negative health effects, including inhibited growth, reduced photosynthesis rates, sunscald, wilting, and even death. Different crops exhibit varying levels of sensitivity to heat stress, but corn—a staple crop for billions of people—is particularly vulnerable. As extreme heat stress events increase in frequency and intensity, national and global food security is put at risk. Facing this challenge and understanding the effectiveness of alternative strategies to overcome it is precisely what drove Haqiqi to pursue his research.

Climate impact on average crop production has been researched to no end. There are many studies that look at the effects of heat stress or other extreme weather events on average corn yield. The problem, according to Haqiqi, is that looking at the average can be misleading and neglects a large part of the risk.

“A lot of other studies have looked at this problem and determined that, on average, crop production will be a little bit lower,” says Haqiqi. “But I find that looking at the average is misleading. Mixing extreme highs with extreme lows, for example, means that, on average, everything might be fine. What we need to do is study the volatility, because that’s where the real risk is. If we want to prepare, we have to measure the volatility, not just the average.”

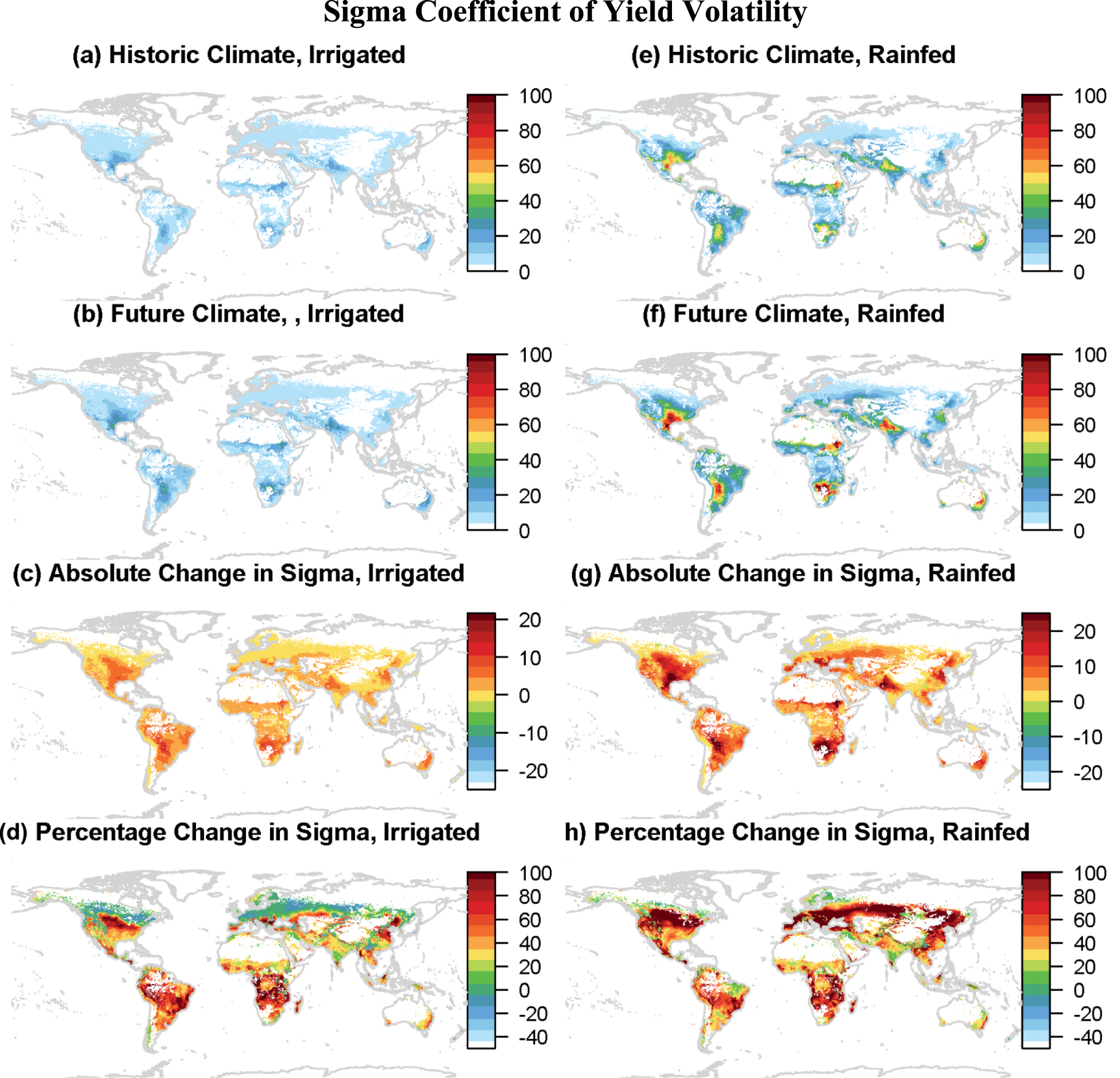

While a small decrease in average annual corn yields may not be considered problematic, increased volatility is. Volatility always has been and always will be a factor in crop production. Some years will be worse than others. But as the risk of extreme weather events decimating a crop supply increases, so too does the chance that any particular season will cause the global supply of food, not to mention the agricultural market, to implode. Haqiqi’s goal was to investigate future volatility and risk in corn production associated with increased heat stress, as well as evaluate the effectiveness of two different adaptation strategies—irrigation and market integration.

Irrigation is a tried-and-true method of reducing crop vulnerability during periods of extreme heat. Not only does it cool the temperature of the plant, it also maintains appropriate soil moisture levels, which improves nutrient uptake, photosynthesis rate, and biochemical efficiency. The problem is that wide-scale adoption of irrigation as an adaptation strategy would further deplete an already strained resource—water. This concern over groundwater depletion has led to a growing interest in trade as an alternative option for offsetting crop volatility risk.

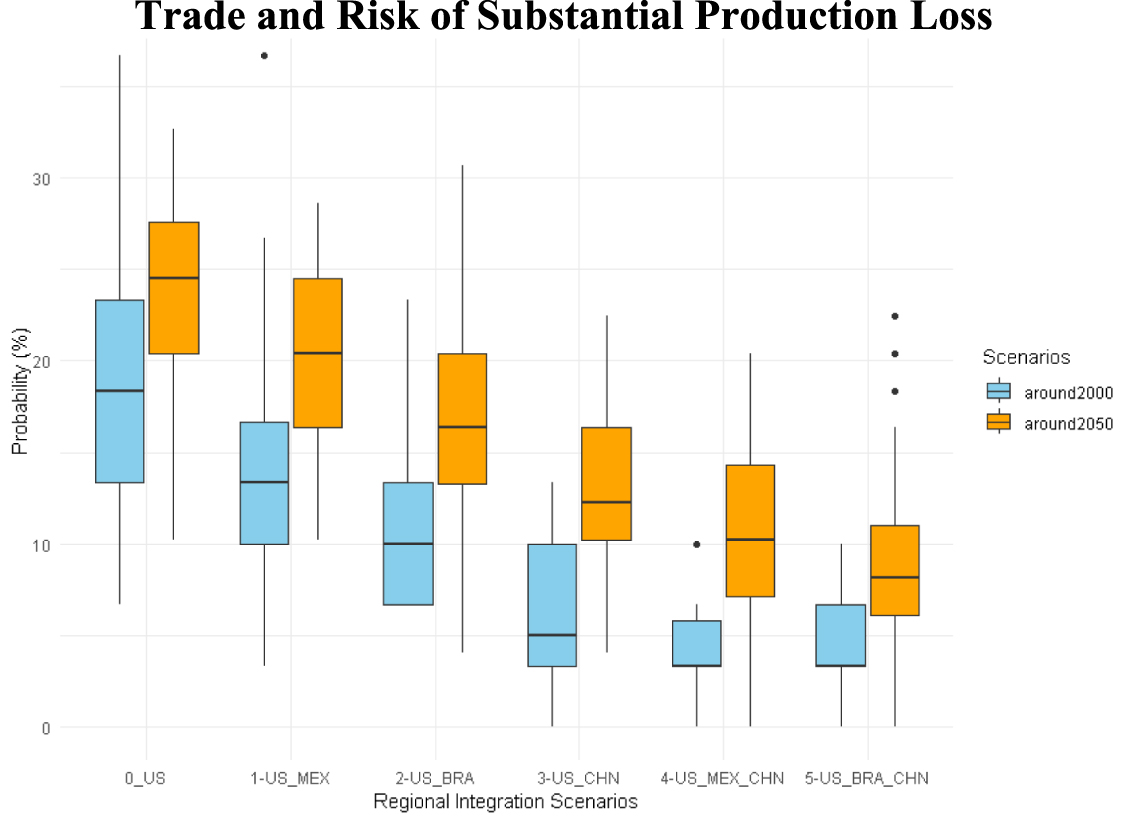

International trade partnerships between regions with differing climate patterns could reduce the risk of substantial losses to the national corn supply, but trade as an adaptation strategy had only been discussed in theory. Haqiqi wanted to measure the strategy’s effectiveness quantitatively. To begin, he needed to predict how corn yields would be affected by potential changes to the climate patterns. Haqiqi used a statistical panel model to estimate corn yield response to heat stress and then combined those results with NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 climate data to project future production volatility and risks of substantial yield losses. To assess overall volatility, Haqiqi needed to calculate the extreme heat levels (i.e., not the average) of each day for millions of fields worldwide, aggregate this for each growing season in every region that produces corn, and then aggregate this to determine global corn supply. Haqiqi then converted these from daily to yearly calculations and determined year-on-year changes in volatility. These results were then used to determine the risk of substantial loss of production for each region. Haqiqi also assessed the relative volatility of each region compared to the global market. Once these baseline results were obtained, Haqiqi could simulate multiple scenarios to analyze irrigation and market integration for their ability to reduce these future risks.

The results of  Haqiqi’s research were clear: 1) corn yields will experience higher volatility due to increased heat stress; 2) irrigation expansion can offset this risk; 3) trade can also buffer the risk, but without depleting the groundwater supply. The third point is salient—according to the numbers, irrigation in the US will need to rise from 15% of farm land to 50-75% in order to maintain historical risk levels, which is unsustainable.

Haqiqi’s research were clear: 1) corn yields will experience higher volatility due to increased heat stress; 2) irrigation expansion can offset this risk; 3) trade can also buffer the risk, but without depleting the groundwater supply. The third point is salient—according to the numbers, irrigation in the US will need to rise from 15% of farm land to 50-75% in order to maintain historical risk levels, which is unsustainable.

“So the whole idea of this paper was to show that, yes, there are some temporary solutions, like irrigation, but they are not sustainable,” says Haqiqi. “Something else, like international trade, which is a solution from an economic perspective, can have a similar effect in terms of reducing volatility and risk. But also, it has benefits because you don't need to have a lot of unsustainable use of resources.”

Haqiqi’s research required a massive amount of computing power, and for that, he relied on Anvil. The supercomputer was used for all computational tasks involving yield projection, variability analysis, and risk assessment.

“Without Anvil, this paper would be just a conceptual framework that, hey, you know, trade could be a good thing compared to irrigation,” says Haqiqi. “But we didn't have numerical evidence to support that claim. Now, thanks to having access to Anvil, we could provide that evidence.”

Haqiqi went on to note that the support he received from the Anvil team was exceptional and that because of the quick, comprehensive responses to his support tickets, he was able to rapidly move past any issues he had.

The results of Haqiqi’s research were published in Environmental Research: Food Systems. To view the publication and learn more about the study, please visit: Trade can buffer climate-induced risks and volatilities in crop supply.

To learn more about High-Performance Computing and how it can help you, please visit our “Why HPC?” page.

Anvil is one of Purdue University’s most powerful supercomputers, providing researchers from diverse backgrounds with advanced computing capabilities. Built through a $10 million system acquisition grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Anvil supports scientific discovery by providing resources through the NSF’s Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS), a program that serves tens of thousands of researchers across the United States.

Researchers may request access to Anvil via the ACCESS allocations process. More information about Anvil is available on Purdue’s Anvil website. Anyone with questions should contact anvil@purdue.edu. Anvil is funded under NSF award No. 2005632.

Written by: Jonathan Poole, poole43@purdue.edu