Anvil used to study dark matter and early universe formation

Purdue University’s Anvil supercomputer was used by researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to study the effects of dark matter on galaxy formation in the early universe. This research, part of the Supersonic Project, aims to provide a more precise understanding of the galaxy formation process by accounting for a previously overlooked but important factor—the stream velocity.

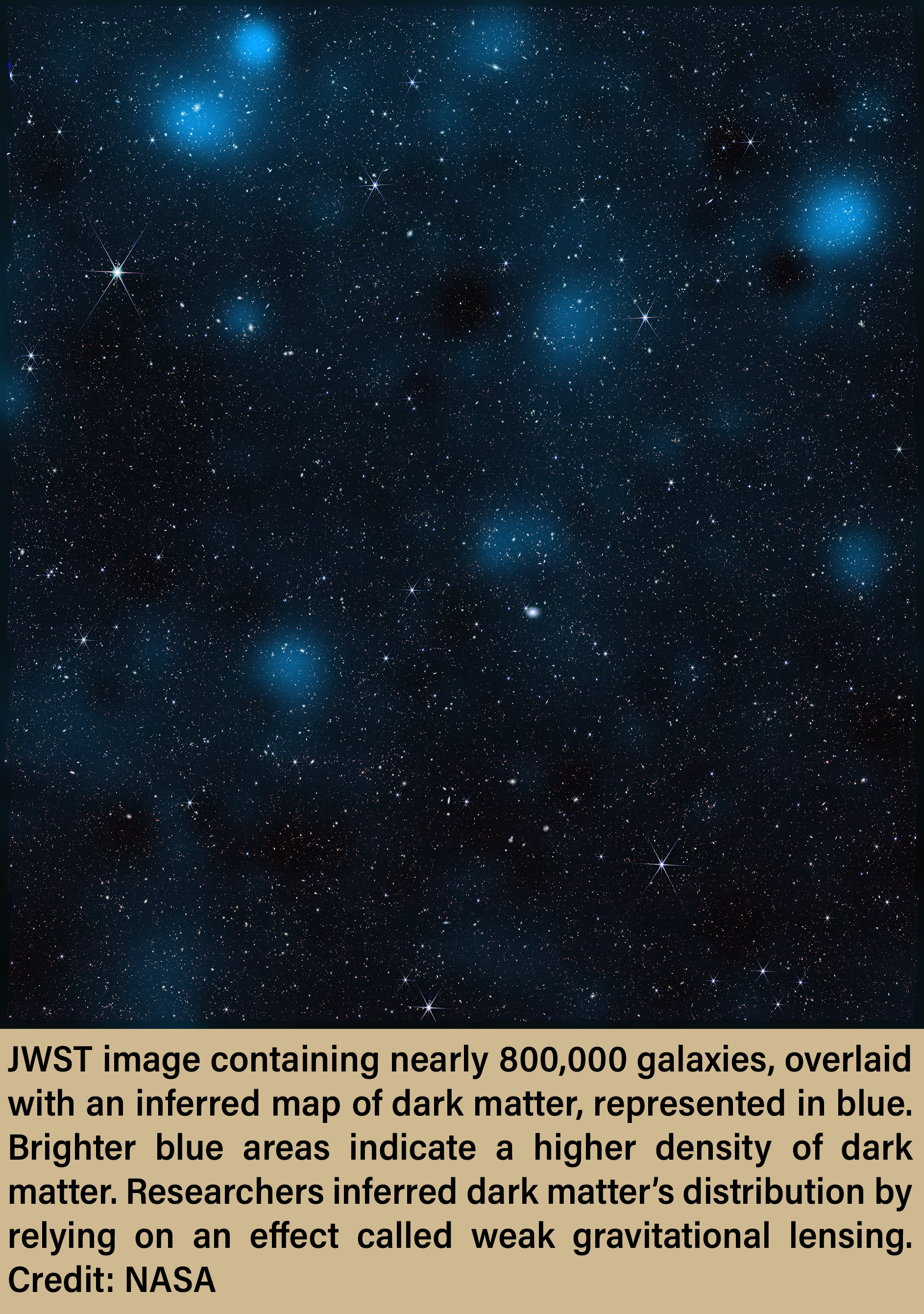

Dark matter is elusive. We don’t know what it is or what it is composed of. This mysterious material scoffs at the adage “Seeing is believing”—it does not interact with the electromagnetic force, meaning it neither absorbs, reflects, nor emits light of any kind. We literally cannot see it, yet we know it is there. Dark matter has mass, thereby exerting the effects of gravity on visible matter. It is only by observing these gravitational effects that scientists know dark matter exists. In fact, dark matter accounts for roughly 85% of all matter in the universe, serving as a cosmic scaffolding that organizes galaxies at scale. Without it, galaxies would have long ago been torn asunder by their own rotational velocities, lacking the necessary gravitational pull required to hold together.

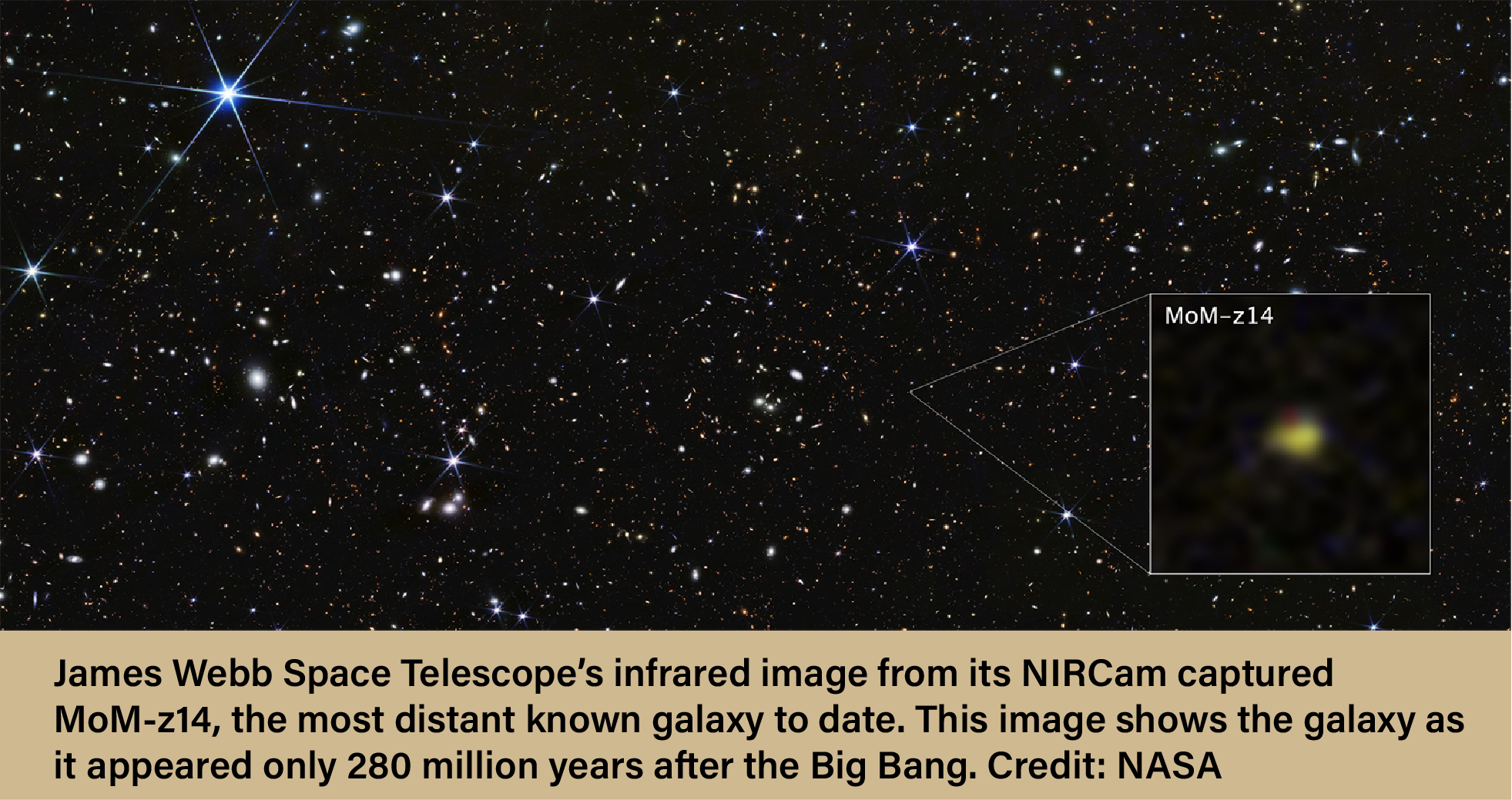

As one can imagine, studying a material that can’t be seen but whose effects must be observed through a telescope can be tricky. For decades, scientists have tackled this problem by running cosmological simulations that include dark matter and comparing them to what is actually seen in the universe. If the end result of a simulation matches the physical reality seen through the telescope, then that’s a good sign that the scientists are on the right track with their theories. If not, the theory must be altered or dismissed entirely. Recent technological advances have enabled scientists to study dark matter in greater depth than ever before. High-performance computing (HPC) systems provide an astonishing amount of computing power, while the new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) gives astronomers an unprecedented view of the universe, enabling observations of the first stars and formation of the first galaxies after the Big Bang. This boost in data-gathering ability and computing performance lies at the heart of the dark matter research being conducted at UCLA.

Claire Williams is a PhD student in the Astronomy and Astrophysics Division of the UCLA Department of Physics and Astronomy. Williams’s focus is on theoretical astrophysics. She is part of the Supersonic Project, a collaboration that studies how stream velocity and dark matter affected galaxy formation in the early universe. In this instance, stream velocity refers to the relative velocity of baryons and dark matter during the early formation stages of the universe. The stream velocity has been largely neglected in traditional simulations of galaxy formation. However, recent findings show that the stream velocity was supersonic, which had major implications for how the baryons and dark matter were distributed. Williams’s, and the rest of the research group’s, goal is to improve our understanding of the galaxy formation process by including the stream velocity as a factor in their cosmological simulations.

“So our specific studies are trying to gain a more precise understanding of the process by including effects that previously nobody included,” says Williams. “People already had dark matter, they already had gas, but they were missing the stream velocity. It has been largely ignored because it is challenging to get right in simulations. But neglecting the fact that material was moving past the dark matter at five times the speed of sound inevitably leads to a different result. What our group has done is to run simulations that correctly include the relative motion of dark matter and ordinary matter at early times in the universe.”

Williams and her research group utilize the Anvil supercomputer to run high-resolution AREPO hydrodynamics simulations for a number of different studies. The common theme across these studies is that the group runs theoretical simulations both with and without stream velocity as a factor, and that the results are, or will soon be, compared with JWST observations. The size of the regions being simulated are, quite literally, astronomical, ranging upwards of two megaparsecs. This equates to a volume slightly larger than the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies combined. The simulations are also incredibly detailed, with each individual particle representing an area roughly 200 times the mass of our sun. For comparison, that’s a single grain of sand on the beach. Simulations this large require a massive amount of computing power and would be impossible without HPC resources like Anvil.

“So we're simulating a region larger than the whole Milky Way, but our individual pieces that are moving around are only a couple 100 times bigger than our own sun,” says Williams. “This is why we need Anvil, because you couldn't run this on your laptop. This takes a couple of weeks to run on the cluster.”

Running the simulations is only the first part of the process; HPC resources are further needed to actually analyze the data. Williams continues:

“Then, at the end of the day, when you finish your simulation run, you basically have a bunch of imaginary particles in an imaginary box. But you have to figure out, ‘How would these particles translate to light that the telescope would see?’ So you need to post-process the simulations, which involves extensive data analysis and specialized algorithms to convert the resulting particles into light in space. We need Anvil for this data analysis as well.”

The end  result of the group’s computational work is a theoretical picture of what the universe should look like to us today, as viewed through the JWST. Dark matter was dispersed throughout the universe soon after the Big Bang, unaffected by the forces of electricity and magnetism. The gravitational pull of dark matter led to clumps of particles, which eventually formed into galaxies. And the precise placement of these galaxies was likely influenced directly by the stream velocity. At least, that’s Williams’s hypothesis. Now, the research group must wait to see if it proves true.

result of the group’s computational work is a theoretical picture of what the universe should look like to us today, as viewed through the JWST. Dark matter was dispersed throughout the universe soon after the Big Bang, unaffected by the forces of electricity and magnetism. The gravitational pull of dark matter led to clumps of particles, which eventually formed into galaxies. And the precise placement of these galaxies was likely influenced directly by the stream velocity. At least, that’s Williams’s hypothesis. Now, the research group must wait to see if it proves true.

“So one of the things that we have found with our studies,” says Williams, “is that the stream velocity should cause some very faint galaxies to shine very brightly for a brief period of time at the beginning of the early universe, because it causes them to form a bunch of stars all at once. Without the stream velocity factored in, you wouldn’t expect to see this happen. And now they're starting to make observations with the JWST that should show what we predict to see. So, hopefully, in the next few years, we can get confirmation from the telescope that this effect is happening.”

Williams continues, “One thing that's kind of cool is that if they don't see that effect, then it poses a big problem for dark matter in general, because all of our models so far are dependent on how we think dark matter should work. So if we make this prediction and the telescope doesn't see it, then we know we've messed up our collective understanding of dark matter along the way and may need to make changes to things we thought we had a grasp on in our cosmology.”

For more information about William’s research, please visit her UCLA Bio Page. More details on the Supersonic Project can be found here: The Supersonic Project

Interested in leveraging the latest advancements in computing to bolster your research? Please visit our “Why HPC?” page to learn more about High-Performance Computing and how it can help you.

Anvil is one of Purdue University’s most powerful supercomputers, providing researchers from diverse backgrounds with advanced computing capabilities. Built through a $10 million system acquisition grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Anvil supports scientific discovery by providing resources through the NSF’s Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS), a program that serves tens of thousands of researchers across the United States.

Researchers may request access to Anvil via the ACCESS allocations process. More information about Anvil is available on Purdue’s Anvil website. Anyone with questions should contact anvil@purdue.edu. Anvil is funded under NSF award No. 2005632.

Written by: Jonathan Poole, poole43@purdue.edu