Researchers use Anvil supercomputer to help detect manipulation in media

In our world of 24-hour news cycles and social media reporting, the amount of information we receive daily has reached astounding levels. Never before has information exchange flowed so freely, nor so quickly, with news from anywhere in the world available instantly at our fingertips. We are dominated by information. And while this is undoubtedly a good thing in many ways, it also leads to a host of complications, thanks to the inaccuracies, manipulations, and misrepresentations that riddle our media. Indeed, trust in the media seems to have reached historic lows, and the prevalence of opinion-driven articles parading as news only exacerbates the issue. To address this problem, two graduate students from City University of New York (CUNY) used Purdue’s Anvil supercomputer to expand research on the trustworthiness of media and how we can utilize artificial intelligence (AI) to determine an article’s intent.

Vivek Sharma is a student at the CUNY Graduate Center, as well as a lecturer at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He, along with fellow student Mohammad Shokri, recently used the Anvil supercomputer to conduct two separate research projects surrounding the topic of media trustworthiness. The first project, led by Sharma, involved using AI for propaganda detection within news articles and social media posts. The second, in which Shokri was the lead, analyzed objectivity versus subjectivity in news articles and evaluated how different large language models (LLMs) detect subjectivity and generalize to out-of-distribution data (data that deviates significantly from the model’s machine learning training sets). These types of research projects are important in that they not only investigate media manipulation, but also how to automate and improve the detection of such manipulations. This, in turn, could lead to the creation of more accurate tools that consumers could use to monitor media reliability.

Propaganda is everywhere. Advertisements, television shows, YouTube videos—and yes, even news articles—often contain some form of propaganda, whether by accident or design. We’ve come to expect it when someone wants to sell us a product or service or even an idea, but we do not expect it from our news sources, where the intent should be to provide us with facts so we can decide our worldview for ourselves. Nonetheless, propaganda has crept into the news. By taking advantage of specific psychological and rhetorical techniques, such as the use of logical fallacies and emotional language, many news outlets are increasingly engaged in shaping how they present their information to promote specific agendas or viewpoints. This is exaggerated even more by individuals who use social media to reach large audiences. The insidious nature of propaganda is that these techniques go largely unnoticed by the consumer. We can pick up a viewpoint or ideology without realizing we have been pushed—or even misled—to “our” conclusions. For this reason, Sharma decided more research was needed on propaganda detection.

Using Anvil, Sharma’s intent was to create a robust machine learning (ML) model that could detect propaganda within a variety of news sources. The team used a data set known as the Propaganda Techniques Corpus (PTC) to train the model. The PTC is a collection of roughly 550 different news articles in which fragments containing one out of 18 propaganda techniques have been annotated. Once the model was trained on Anvil, the research team could use it to scan each line of text within a new data set and detect whether it contained propaganda and, if so, what type.

“For this project, we are solely looking at propaganda detection,” says Sharma. “We are not interested in determining ground truth—the actual factuality of the news—or whether the propaganda was intentional. We're just looking at the text and trying to find out if it has some kind of propaganda or not. Most people, especially the journalists, tend to use some sort of propaganda technique.”

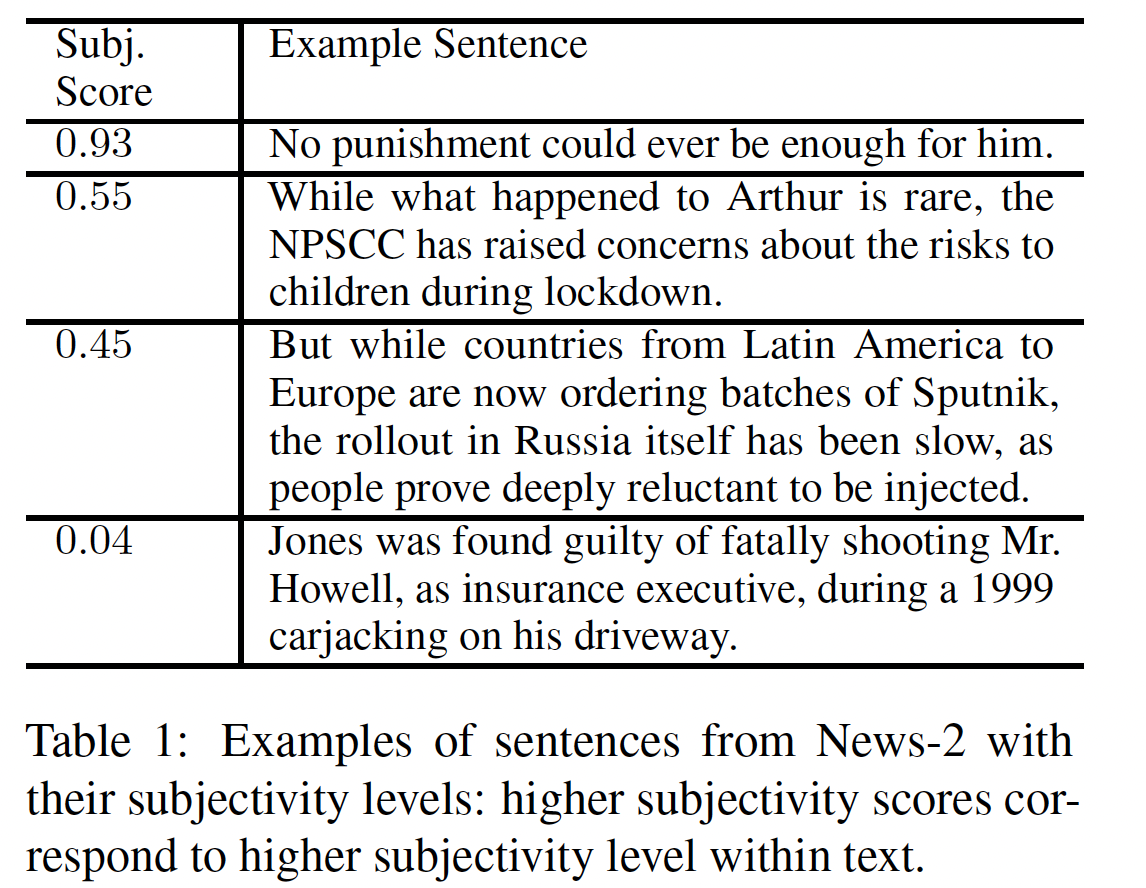

The second project looked into another issue found in the news and the media today—the separation of fact from opinion. Opinion-driven articles can influence a reader’s beliefs to align with the author’s viewpoint. Subjective language is the linchpin for such articles, and also something that fake news and misleading stories rely heavily upon. In developing AI to a point where it can be quickly and easily used to detect subjectivity within text, researchers would provide readers with a tool to help thwart attempts at manipulation.

Shokri took the lead  on the second project with a goal of learning how to create better LLMs for subjectivity detection. The research team examined how different language models detect subjectivity in the news domain and determined where they fail. Specifically, they wanted to know the effects that fine-tuning a language model had on generalization to out-of-distribution data, how well pre-trained, state-of-the-art LLMs detect subjectivity in the news, and how LLM performance can be improved using different prompting methods. The team used three separate data sets to ensure generalizability outside of the training data, and fine-tuned several popular language models to asses the adaptability of each for these data sets. They also analyzed the effects different prompting methods had on the success of their models. By the end of the project, the team had accomplished everything they set out to do and now have an excellent jumping-off point for their next research project, all of which lead toward the ultimate goal of designing a subjectivity detection system that can be used in real-time.

on the second project with a goal of learning how to create better LLMs for subjectivity detection. The research team examined how different language models detect subjectivity in the news domain and determined where they fail. Specifically, they wanted to know the effects that fine-tuning a language model had on generalization to out-of-distribution data, how well pre-trained, state-of-the-art LLMs detect subjectivity in the news, and how LLM performance can be improved using different prompting methods. The team used three separate data sets to ensure generalizability outside of the training data, and fine-tuned several popular language models to asses the adaptability of each for these data sets. They also analyzed the effects different prompting methods had on the success of their models. By the end of the project, the team had accomplished everything they set out to do and now have an excellent jumping-off point for their next research project, all of which lead toward the ultimate goal of designing a subjectivity detection system that can be used in real-time.

Both Sharma and Shokri were thrilled with Anvil’s performance in the projects, noting how useful Anvil’s GPUs were and the benefit of its large memory nodes.

“Training these models requires GPUs and a lot of memory,” says Sharma. “Anvil gives us both of these things, which is great. Trying to train these models on your laptop is unimaginable.”

Sharma continues, “Another good thing about Anvil is that there are so many packages already on the system, so it's super ready for any kind of machine learning task. Most of the time, any package I needed to run an ML task was already on Anvil. Beyond that, Anvil’s support team was great. Anytime I needed help, I emailed the support team and would receive a response really quickly. I even told my supervisor about this, and she was impressed, as other systems that she’s worked on would take days to respond.”

Sharma’s supervisor for the projects was Professor Shweta Jain from John Jay College at CUNY, while Shokri’s supervisor was Assistant Professor Sarah Ita Levitan from Hunter College, both at CUNY. Elena Filatova, an Associate Professor at City Tech College at CUNY, was also part of the research team.

To learn more about HPC and how it can help you, please visit our “Why HPC?” page.

Anvil is Purdue University’s most powerful supercomputer, providing researchers from diverse backgrounds with advanced computing capabilities. Built through a $10 million system acquisition grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Anvil supports scientific discovery by providing resources through the NSF’s Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS), a program that serves tens of thousands of researchers across the United States.

Researchers may request access to Anvil via the ACCESS allocations process. More information about Anvil is available on Purdue’s Anvil website. Anyone with questions should contact anvil@purdue.edu. Anvil is funded under NSF award No. 2005632.

Written by: Jonathan Poole, poole43@purdue.edu