Half of the entire Anvil supercomputer used to challenge traditional turbulence theory for space and climate modeling

Researchers from the University of Wisconsin (UW)–Madison used Purdue’s Anvil supercomputer to study turbulence and turbulent transport in astrophysical plasmas. This research seeks to elucidate the fundamental physics of turbulence, which will have applications across the fields of fluid and plasma dynamics. The group not only pushed the boundaries of scientific research with their work, but also tested the performance limits of Anvil, utilizing upwards of half the machine (512 nodes at once) to run a single simulation.

Bindesh Tripathi, who spearheaded the project, is working toward finishing his doctoral dissertation in the Department of Physics at UW–Madison. Under the joint supervision of advisors Dr. Paul Terry and Dr. Ellen Zweibel, both of whom are professors at the university, Tripathi conducts research involving astrophysics and plasma physics, mathematical/theoretical physics, and numerical methods.

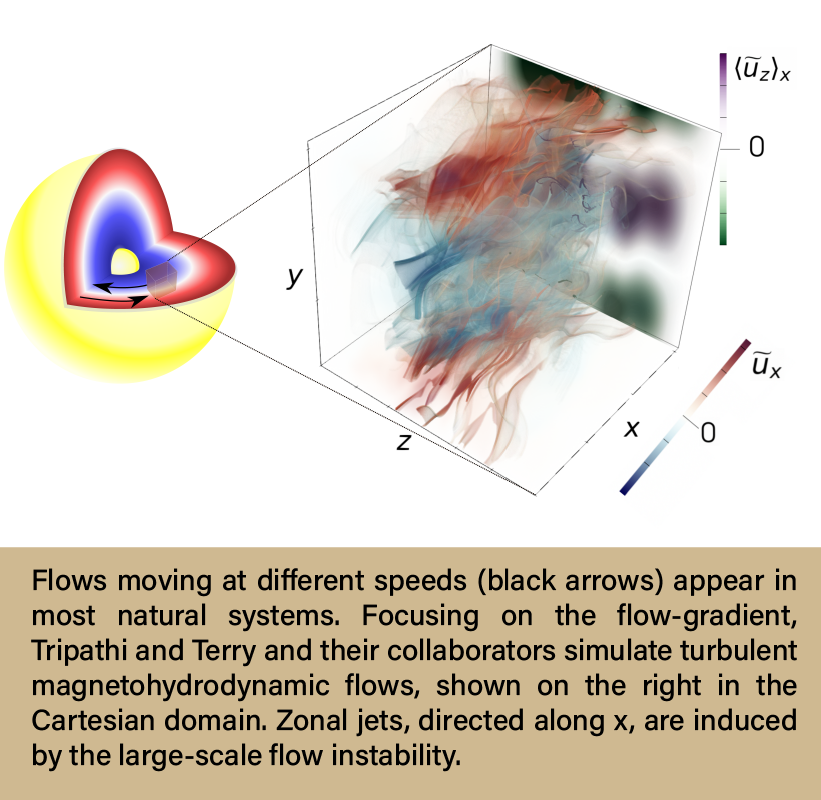

“I study astrophysical plasmas using theoretical models that we have developed over the years, and to test them, we use supercomputers,” says Tripathi. “The problem I deal with most of the time is a problem with flows that go in with different velocities, which creates turbulence. This turbulence can occur on multiple scales—from clouds in the Earth’s atmosphere, to hot, dense gasses in the stars. So I try to understand how these complex turbulent processes can be modeled using a simpler model that can reproduce the comprehensive details of numerical simulations.”

One recent project that Tripathi and Dr. Terry embarked upon was to run plasma turbulence simulations to study the physics of plasmas. The pair—with their collaborators Dr. Zweibel, A. Fraser (Colorado), and MJ Pueschel (the Netherlands)—wanted to investigate the properties that create and determine the structure of magnetic fields at the largest scales observed in the universe. To do this, they focused on the plasma in our galaxy known as the interstellar medium (ISM). The ISM is the plasma in which stars in our galaxy exist. It encompasses the region between stars and contains vast clouds of gasses and minute solid particles. To offer an analogy, if stars are boats floating in the ocean, then both the air and water surrounding the boats are the ISM. The ISM supports electrical currents, which create magnetic fields. These magnetic fields are highly ordered at scales as large as the ISM. The conundrum for scientists stems from the fact that the system is very chaotic at smaller scales, and it is unknown how the system resists transitioning from order to chaos.

“It's been difficult over the years to replicate observations made of large-scale magnetic fields,” says Dr. Terry. “Whenever we apply a model like magnetohydrodynamics to try and understand this process, we find that the system is rather turbulent. The motions are rather disordered and chaotic, which means the currents are rather disordered and chaotic, and so the magnetic fields themselves are rather disordered and chaotic. And it's difficult to solve one of these mathematical models in such a way that you can recover these large-scale, ordered magnetic field structures. So this is something we are trying to understand with the simulations that we're running.”

In fluid and plasma dynamics, turbulence refers to chaotic changes in pressure and flow velocity—turbulent flows contain eddies, swirls, and flow instabilities. In the ISM, turbulence is created by shear flow instability. The instability builds to a critical point within the system, and upon surpassing this point, begins to break the structure down into smaller and smaller scales, creating turbulence. According to Dr. Terry, turbulence is typically very efficient at stretching the magnetic field, bending it, folding it, putting it into smaller scales, and carrying the magnetic energy with it. So the expectation is that this would occur within the ISM. But that is not what scientists have observed. Instead, the magnetic field structure of the ISM remains ordered. Why is this the case? The answer lies in something known as “stable modes.”

Since the discovery of plasma dynamics instabilities and their respective mathematical equations, scientists have also known about the existence of stable modes—flow patterns that, when disrupted, will decay back to their original state. However, until roughly 20 years ago, scientists ignored these stable modes in research because even though they were present within turbulent systems, they were considered inert under such conditions. What researchers—and specifically, Dr. Terry’s group—have found in recent years is that these stable modes are highly active, even in large-scale systems like the ISM. Specifically within the ISM, the stable modes actually counteract the instability, redirecting the energy back into the shear flow gradient that created the turbulence in the first place. This “blocks” the magnetic energy from breaking down into smaller scales, keeping the large-scale structure ordered instead of allowing it to devolve into chaos.

The discoveries of stable-mode excitations were made by Tripathi’s predecessors, who worked in Dr. Terry’s group. Tripathi’s job was to take their research and extrapolate the details—what are the effects of this process? how does it work? etc. In short, Tripathi needed to shed light on the underlying physics of these mechanisms.

To accomplish this  task, Tripathi had to make several bespoke changes to a 3-dimensional (3D) magnetohydrodynamics simulation software known as Dedalus. Tripathi, in collaboration with Dr. Fraser, took Dedalus and developed highly specialized code alterations that could uncover the stable modes in the simulation and highlight their effects on the system. Thanks to Tripathi’s work, the simulations can now account for the individual actions of the instabilities and the stable modes, showing precisely how much motion is the instability, how much is the stable mode, and what is happening to the magnetic energy during the process.

task, Tripathi had to make several bespoke changes to a 3-dimensional (3D) magnetohydrodynamics simulation software known as Dedalus. Tripathi, in collaboration with Dr. Fraser, took Dedalus and developed highly specialized code alterations that could uncover the stable modes in the simulation and highlight their effects on the system. Thanks to Tripathi’s work, the simulations can now account for the individual actions of the instabilities and the stable modes, showing precisely how much motion is the instability, how much is the stable mode, and what is happening to the magnetic energy during the process.

The results from Tripathi’s and Dr. Terry’s work are impressive and will help advance the field of plasma dynamics. However, obtaining these results would have been impossible if the pair had not had access to an extraordinary amount of computing power. The Anvil supercomputer provided them with exactly what they needed.

3D magnetohydrodynamic turbulence simulations are very computationally expensive, requiring massively parallel computations in a way that many problems don’t. To support the researchers’ work, the Anvil team set up a special allocation that allowed the group to utilize 512 nodes at once. The group routinely used 30,000 to 40,000 cores simultaneously. To be clear, this was a parallel code, so one single simulation required the use of all of the cores at the same time. This level of computation for a real-world research problem had not yet been tested on Anvil, but the computer was able to handle it with no issues. Tripathi’s code ran seamlessly, even at such a large scale, and he was thrilled with the performance of the system.

“I ran the Dedalus code, and I found it running beautifully well,” says Tripathi. “Anvil has a large number of cores, and the queue time was relatively short, even for the very large resources that I was requesting, and the jobs would run quite fast. So it was a quick turnaround, and I got the output pretty quickly. I have had to wait a week or even longer on other machines, so Anvil has been quite useful and easy to run the code. Anvil has also generously provided us with storage of a large dataset, which now amounts to 125,000 gigabytes from my turbulence simulations.”

Ordered magnetic fields spontaneously emerge out of chaotic, tangled fields. This finding is consistent with astrophysical observations. Streamlines of magnetic fields are 3D-rendered and are colored red–blue by the x-component of the field. Streamlines of the electric current density are shown in green; color represents magnitude. Poloidal fields are displayed on the (y,z)-plane, after averaging them over the azimuthal (x) direction.

Tripathi’s and Dr. Terry’s work is not only useful for large-scale problems, such as the ISM, but is applicable to any problem involving fluid or plasma dynamics. Water in a teacup, ocean waves, Earth’s atmosphere, black holes, galaxies—the fundamental physics of turbulence apply at any scale, and their work has helped shed light on these mechanisms. The group has published their research surrounding fluid dynamics and plasma dynamics in multiple scientific journals. One particularly important paper, in which they solved the famous Navier-Stokes equation (a fluid dynamics model), was published in Physics of Fluids, and can be found here: Three-dimensional shear-flow instability saturation via stable modes. They are working on reporting novel results from their 3D magnetized turbulence simulations that they performed on Anvil. Their recent 2D magnetized turbulence analyses were published in Physics of Plasmas; the publication was selected by the journal Editors as a Featured article, which can be found here: Nonlinear mode coupling and energetics of driven magnetized shear-flow turbulence

The research highlighted in this article was funded by the National Science Foundation under Award 2409206 and Department of Energy Grant DE-SC0022257 through the DOE/NSF Partnership in Basic Plasma Science and Engineering.

To learn more about High-Performance Computing and how it can help you, please visit our “Why HPC?” page.

Anvil is one of Purdue University’s most powerful supercomputers, providing researchers from diverse backgrounds with advanced computing capabilities. Built through a $10 million system acquisition grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Anvil supports scientific discovery by providing resources through the NSF’s Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS), a program that serves tens of thousands of researchers across the United States.

Researchers may request access to Anvil via the ACCESS allocations process. More information about Anvil is available on Purdue’s Anvil website. Anyone with questions should contact anvil@purdue.edu. Anvil is funded under NSF award No. 2005632.

Written by: Jonathan Poole, poole43@purdue.edu